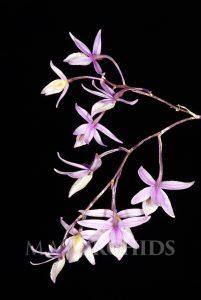

Barkeria strophinx

Barkeria strophinx

Barkeria strophinx (Rchb. f.) Halb.

Common name: The Axle or Pivot Barkeria

Synonyms:

Homotypic name:

Epidendrum strophinx (1876)

Barkeria naevosa subsp. strophinx (1974)

Distribution

A caespitose, erect deciduous herb with an epiphytic habit that grows between 15-75 cm. Roots: flattened, gray. Stems: thin, fusiform, pedunculate (stalked), grayish-white, with 4-5 internodes, 2-25 cm. in length. Older stems are covered with scarious, papery bracts. Leaves: 2-6 linear-lanceolate, acuminate, distichous, subsucculent, present only on the newly developing growth and appressed to the stem via an articulated joint. Inflorescence: terminal, erect, frequently arching, panicle (rarely a raceme), from the new growth, on an elongated subterete, rather thin peduncle with 5-9 internodes covered by tubular bracts (scarious at anthesis), from 6.5-35 cm in length with 3-60 flowers arranged in a horizontal plane. Flowers: Attractive, resupinate, sweetly fragrant, 1.4-2.6 cm diameter spread, with the tepals straight and extended in the same plane and held over the descending lip. Color of the segments is variable in the population ranging from pure white to dark magenta with intense color saturation. Sepals are usually somewhat darker than the petals with darker venation evident. Lip is white, greyish-white or yellowish with magenta pigmentation over the raised veins and margins. Sepals are subequal, extended, lanceolate, acute-acuminate, with seven conspicuous parallel veins, incurved or flat with the margins reflexed making them concave. Petals are lanceolate, acuminate to obtuse, with five parallel vein, in the same plane as the dorsal sepal and positioned at a 45° angle to it. Both lip and column point down in their natural configuration. The lip is entire, ovate, acuminate, acute, basally cuneate, fused to the column, strongly concave with the basal margins raised and incurved, and the apex is extended or deflexed. Callus is a white, raised platform, deeply sulcate to form a fovea with three longitudinal rows of white or transparent warty or papillose veins that extend forward but do not reach the apex. The subtrigonous column is winged, short, pinkish or purple-red apically but green at the base, somewhat incurved, dorsiventrally flattened into a flabellate outline with a truncate but relatively wide apex with three teeth. The ventral surface of the column is convex and longitudinally sulcate. Anther is reddish and the same color as the apex of the column.

There continues to be some confusion as to where the species grows based on an error made by Federico Halbinger. Halbinger wrote that he found the species in “Tingambato, Michoacan” in an “Orquidea” article that he authored in which he reduced the taxon in rank to being a subspecies of B. naevosa. However, the authors of this website spoke with Halbinger before his passing and he said that the Tingambato that he referenced was not the municipal capital in the north central part of Michoacan, but was rather a tiny pumping station along the Cutzamala System, a vast hydrologic project that pumps potable water from western Mexico State to Mexico City. The small hamlet of Tingambato lies right on the border with Michoacán and Mexico State, but it is technically in Mexico State. When Halbinger was told of this discrepancy he replied that if that is the case then the species must be reported to be endemic to Mexico State and not Michoacán.

There was also some confusion in Hamburg, Germany at the botanic garden where H.G. Reichenbach filius received the type specimen from Schiller as he was working on the description for the new species. The specimen was annotated as being collected in Guatemala, but no plant of B. strophinx has ever been located there and even its close cousin, B. naevosa only grows as far south as Oaxaca.

Barkeria strophinx has a very restricted distribution as it is known only from the foothills around the Sierra de Nanchititla Mountains in Mexico State. There is supposedly an herbarium specimen from Huetamo, Michoacán that references a plant collected on the northwest side of the Nanchititla mountain range but we have been unable to find it or examine it. As of this writing, the species should be considered endemic to Mexico State, as all of its known stations are located wholly within the borders of that state. However, the stations are so close to both Guerrero and Michoacán that it would not be surprising for future botanical explorations to find this species in these neighboring states, particularly since suitable habitat for this species can be found on opposite sides of the border.

This species could be considered rare but only as a function of its extremely restricted distribution. It is known from only a handful of stations in Mexico State, but at these localities robust populations can usually be observed, especially if they are along river courses.

At lower elevations between 550-650 meters it is very uncommon. It can be found growing on solitary trees of Pithecellobium dulce and Crescentia alata in tropical savannas or cattle ranches. In these conditions the plants are exposed to full sunlight and tremendous heat because the trees have lost their leaves in the dry season and so the population density is as low as one plant per every 10-15 trees. At higher elevations (700-950 meters) this species grows in gallery forest in trees and branches that overhang streams. With more propitious conditions, the populations can be huge and it is possible to find hundreds of specimens per hectare.

Found between 550-950 meters in elevation. It is a very hot-growing species and the areas where it grows are extremely xeric during the dry season. The plants growing along the side of dirt roads are frequently covered with a thick layer of dust from passing vehicles.

In the field near its highest elevation limit of 1000 meters, plants of B. strophinx can sometimes be found sympatrically with B. uniflora. At this elevation in Mexico State, B. strophinx is growing at its maximum altitude, while B. uniflora is growing at its minimum altitude and so their populations intermingle but only in a very narrow altitudinal band. In this zone it is even possible to find the plants growing adjacent to each other on the same tree branches. Even without flowers the plants are quite distinct in that B. strophinx has fusiform pseudobulbs and highly branched inflorescences that begin branching very low on an abbreviated peduncle. In contrast, B. uniflora has cane-shaped pseudobulbs that are the same width throughout its entire length and the inflorescences only branch distally. In Mexico State there is another species of Barkeria, B. obovata, which grows similarly to B. strophinx and in very similar environments, but it only grows above 1000 meters so they are perfectly separated by altitude. It is very difficult to distinguish B. strophinx from B. obovata using only vegetative characteristics but their method of branching is quite distinct as the flowers in B. obovata are crowded toward the distal end whereas the flowers in B. strophinx develop at multiple points along the length of the rachis. Additionally, sometimes it is possible to find plants with seed capsules still developing, and if so then a close examination can reveal the presence of a sac-like nectary at the distal end of the ovary; but only in the case of B. strophinx as this feature is missing in B. obovata. Some writers have claimed in the past that B. strophinx is of hybrid origin, with B. naevosa and B. palmeri being the putative parents, but the evidence does not bear this out. First, the two species are not sympatric at any point in their ranges and it is inconceivable (pun intended) for them to have exchanged genes. Second, if there were only a few specimens of B. strophinx ever observed in the wild then infrequent cross-specific hybridization could be a mechanism to explain such low population numbers, but our observations indicate large, stable populations of similar-looking plants which appear to be inter-breeding naturally. The anatomical differences between B. strophinx and B. naevosa also are heritable and unchanging across generations, so this taxon meets all of the conditions established for both of them to be considered “good” species and not subspecies. (For a more in-depth discussion of tips to distinguish this species from B. naevosa please see the relevant section under that species.)

It blooms in the driest months between January and April, right before the start of the rainy season. Its peak bloom time is between February 15th and March 15th since that is when most plants can be observed in bloom in its native habitat. The plants are able to rebloom from dormant nodes on the rachis if they receive suitable moisture and so in ex-situ conditions in greenhouses it is possible to keep the plant flowering into May or even June. This is not recommended, though, since the size of the pseudobulb that later develops is deleteriously impacted as a result of initiating growth so late in the season.

Owing to its very restricted distribution it is classified as endangered by the Mexican government. Nevertheless, it forms large colonies at its stations and its populations can be quite large. Since it grows in an area of Mexico State that has a heavy presence of illicit cartel activity throughout the year, we are pleased to report that it is under no collection pressure whatsoever.

The number of plants of B. strophinx in cultivation is tiny and only a handful of collectors in Mexico are known to have this species in their collections. A few plants made their way to Germany and Switzerland in the 1980s via Federico Halbinger who spoke fluent German and maintained contact with collectors in Europe. This species is one of the most difficult species in the genus for a collector to find and it is not surprising that it has no reported hybrids. But B. strophinx has very floriferous panicles of star-shaped flowers and it should be used in crosses to see if this characteristic can be transmitted to hybrids. Thinking about this species as being only a retrograde or inferior B. naevosa is a mistake because B. strophinx produces more flowers than B. naevosa even if each individual flower is not as large.