Barkeria melanocaulon

Barkeria melanocaulon

Barkeria melanocaulon A. Rich. & Galeotti

The Dark-stemmed Barkeria

Synonyms:

Homotypic name:

Epidendrum melanocaulon (1862)

Heterotypic name:

Barkeria halbingeri (1973)

Distribution

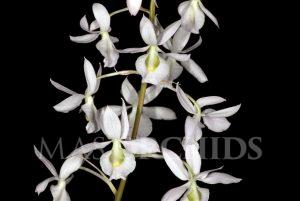

A slowly creeping or subcaespitose deciduous herb with a lithophytic, rarely epiphytic, growth habit and reaching 75 cm. in height. Roots: thickened, terete, long, minimally branched, white in color with green tips. Stems: grayish-white, thickened, laterally compressed with 3-8 internodes, 3-15 cm. in length. Older stems are covered with scarious, papery bracts while the newly developing stem is covered by imbricating folicaceous and non-foliaceous bracts. Leaves: 3-6 elliptic to narrowly ovate, coriaceous to subsucculent, present only on the newly developing growth and connected to the tubular clasping stem bracts via an articulated joint. Inflorescence: terminal, erect raceme, 12-60 cm. in length, thin, greenish-purple in color and with 3-25 non-fragrant

flowers. Flowers: Showy, concolorous, 2.5-4.0 cm in diameter, pale lilac to pink in coloration with broad segments. The dorsal surface of the column is greenish-yellow and suffused with dark purple blotches over its entirety with large, prominent wings. The sepals are elliptic to oblong, erect, and reflexed. Petals are upward-facing, broadly elliptic, and slightly recurved. The lip is

ovate-cordiform to ovate-subrectangular, fused to the base of the column, with the tip truncate and emarginated. The basal part of the lip clasps the column, the midlobe is generally flat while the distal portion is raised, conduplicate and with undulating margins. The callus is white with three longitudinal keels, the middle one is the most prominent and extends to the apex.

Endemic to Oaxaca, Mexico but with a very restricted range that includes only the inland slope of the Sierra de Juarez and some areas in the Central Valley near the capital city.

Very rare. In its native range the plants do not form colonies but rather individual plants can be observed that are separated by as much as 100-250 meters from other specimens. Additionally, the plants do not form large specimens and this may indicate that their lifespan is relatively short. The population near Mitla was almost wiped out by zealous over-collecting after Federico Halbinger publicly revealed the locality in the mid-1970s, but reports by Soto Arenas (2002) that the population there was completely extirpated are incorrect. Interestingly, the original description by Richard and Galeotti in 1845 also mentions that the plants are very rare for which we can assume that the populations of this plant were never common and its present-day scarcity is not solely the result of anthropogenic pressure.

Barkeria melanocaulon inhabits the ecotone between dry oak forests and tropical deciduous forest or Bursera scrub. The growing habit of the plants can be either lithophytic or epiphytic but most plants are rupicolous. As rupicolous plants they grow interspersed on limestone outcroppings along with Hechtia,Tillandsia and arborescent cacti. These rock gardens are usually protected from full sun exposure by their location at the bottom of canyons, since the high cliff walls shield them from the blazing sun for most of the day. Alternatively, the plants will sometimes colonize directly on the calcareous walls of the cliffs. These plants generally grow close to the ground and one of their more successful growing strategies is to alight at the base of Bursera or Pseudosmodingium trees at heights of no more than 50 cm. and allow their naked roots to grow down the trunk and into piles of decomposing leaves. Similarly, they may colonize the leaf tips of large bromeliads but their roots will meander into the “wells” between the leaf axils to find retained rainwater and organic matter. They are rarely seen as branch or twig epiphytes.

1600-1800 meters above sea level.

This seems to be the most frequently misidentified species in the genus. The reason for this can be attributed to an innocent mistake made by Federico Halbinger when he viewed the drawing for the type material collected by Richard and Galeotti for Barkeria melanocaulon and noted that the pressed specimen had a lip divergent from the column, a trait more typically associated with Barkeria whartoniana. The original specimen was lost, but the drawing showed three things: A) a divergent lip as already noted B) very dark venation patterns in the floral segments and C) an emarginate (notched) lip. Apparently what happened is that the original description by Richard and Galeotti used observations made not on the basis of fresh, field-collected specimens, but dried herbarium material. This explains the prominent veins on the sepals and petals that become readily apparent on dried specimens but are rarely visible on fresh flowers. The shape of the lip of that dried specimen is a perfect match for the Barkeria species from central Oaxaca that we now recognize as Barkeria melanocaulon. As for the atypical flowers with their divergent lips, what explanation can be given to explain this phenomenon? When a three-dimensional flower is flattened its morphology changes because of the force applied. Soto Arenas (1993) argues that when the flowers were pressed that the lip was pulled away from the column and the flowers subsequently dried in that position. Thus, the type specimen of Barkeria melanocaulon that Halbinger examined with what we now think were flowers with artificially manipulated divergent lips correctly referenced plants from central Oaxaca. Since he did not realize how the column had come to be shifted away from the column, he mistakenly confused this taxon with material of a Barkeria from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec with a naturally divergent lip, a species that we now recognize as Barkeria whartoniana. The end result is that for about 20 years the taxon that we now know as Barkeria whartoniana was known as Barkeria melanocaulon and what we now recognize as Barkeria melanocaulon was described by Halbinger as a “new” species, Barkeria halbingeri!

In reality, Barkeria whartoniana is the easiest species in the genus to identify because it is the only one that does not have the lip firmly appressed to the column along its entire length. When you see plants with that characteristic they are instantly recognizable, and this trait can be used on its own to make a correct determination. Namely, anything with a divergent lip is automatically assumed to be Barkeria whartoniana, whereas all other species with an appressed lip are something else.

Regarding the clues that can assist in correctly identifying the remaining species in the genus, Barkeria melanocaulon has concolorous flowers, a telltale characteristic that only Barkeria scandens and Barkeria skinneri also exhibit; but these last two species have flowers with an intense magenta color as opposed to the pale lilac or pink of Barkeria melanocaulon which makes it unlikely that they could be confisued. The remaining species in the Scandens section of Barkeria all have pointed lips which easily differentiate them from Barkeria melanocaulon with one notable exception: Barkeria fritz-halbingeriana. Barkeria fritz-halbingeriana can be confused with Barkeria melanocaulon on account of its pale lilac flowers and truncate lip, but it has a few subtle differences that make them easy to tell apart. Barkeria fritz-halbingeriana has a branched inflorescence whereas the flower spike of B. melanocaulon never branches; and B. fritz-halbingeriana readily forms adventitious keikis on the peduncle, but Barkeria melanocaulon never does. What about their flowers? Those of B. fritz-halbingeriana are smaller with narrower segments, the column is only spotted on the edges of the wings and not dorsally as in B. melanocaulon, and the lip of B. fritz-halbingeriana has a darker distal blotch on the tip while the lip in B. melanocaulon is uniform in color. One last distinguishing characteristic to note would be that only Barkeria spectabilis and Barkeria melanocaulon produce flowers in late spring or early summer on developing or newly-developed growths. This can be an important distinguishing characteristic since all other Barkeria species are fall/winter bloomers.

In its native habitat, it blooms during the summer rainy season from June to August, but in collections the flowers tend to appear much earlier during late spring (April-May). We know of a few specimens that will naturally bloom twice in the same calendar year although this characteristic is extremely uncommon. The second flower spike is always on an additional growth and not just a second flush of flowers that appears on the original flower spike. In these atypical plants, the first bloom will occur in late May right as the rainy season begins and the second will develop in September-October as the rainy season is ending.

The species is highly prized by collectors because of its ease of culture and beautiful, long-lasting flowers. As such, it is highly vulnerable owing to the small size of its populations and their restricted distribution range. According to the Mexican government, this species is classified as endangered. Its saving grace may be that specimens do not form large colonies and hence are extremely difficult to locate in the wild when they are not in bloom, Its scattered biogeographic distribution also means that they are easily overlooked.

Barkeria melanocaulon contributes many desirable characteristics to its progeny, which is one of the reasons that genes from this species are found in many Barkeria hybrids. Because the plants are compact and subcaespitose with thick, sturdy pseudobulbs and wide leaves, the resulting hybrids are more elegant and attractive on account of the plants being more aesthetically balanced. This species comes from an intermediate climate and so is adaptable to being grown in both hot and cool greenhouses. The flower spikes are strong and erect with the flowers having broad petals. The flowers are nicely distributed along the distal end of the inflorescence in attractive shades of pale lilac or pink with intense, dark mottling on the column’s surface. The coloration of the column is strongly hereditary and this is a telltale clue of the hybrid’s provenance. This intense pigmentation of the column is striking in hybrids particularly if the rest of the flower is pale pink or white.