Barkeria uniflora

Barkeria uniflora

Barkeria uniflora (Lex.) Dressler & Halb.

The Single-flowered Barkeria

Synonyms:

Homotypic name:

Pachyphyllum uniflorum (1825)

Heterotypic names:

Barkeria elegans (1838)

Epidendrum elegans nom. illeg. (1862)

Distribution

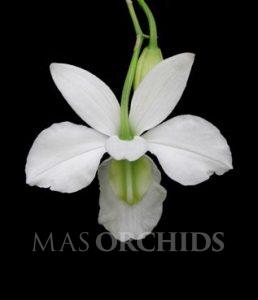

An erect, subcaespitose, deciduous herb with an epiphytic habit growing between 15-100 cm. in height. Roots: flattened against the porophyte host or subterete, long, rarely branched, grayish-white in color with green tips. Stems: grayish-white, slightly thickened, fusiform with 4-9 internodes, 3-26 cm. in length. Young, developing stems are green sometimes with purplish-red streaks while older stems are covered with scarious, papery bracts. Leaves: 2-7, distichous, linear to lanceolate, acuminate to subacute, succulent but still flexible, present only on the newly developing growth and appressed to the stem via an articulated joint. Leaves are olive-green sometimes with reddish-purple streaks. Inflorescence: terminal, erect, lax, pauciflorous panicle with 2-3 branches (rarely a raceme), from the new growth, on a peduncle covered by tubular bracts (scarious at anthesis), 5-50 cm. in length with 1-35 successive flowers with 3-8 open at any time. Flowers: attractive, resupinate, inodorous, 3.5-8.5 cm diameter spread, lip and column descending in their natural positions. Tepals are lilac-pink to white blushed with pink with the interior surfaces conspicuously lighter than the exterior, and extended over the lip in a fan-shaped arrangement. Sepals are subequal, arched, concave, with 7-9 veins, narrowly elliptic to lanceolate and acute to subobtuse. Petals are wider than the sepals, extended, rhombic-obovate to elliptic-ovate, acute to obtuse, basally cuneate, with nine veins, apically either convex or concave and longitudinally sulcate on the dorsal surface. Lip is white or very pale pink with a flabellate or transversally elliptic magenta blotch near the apex, basally fused to column, obovate to subpandurate, entire, lateral margins round or emarginated, convex with the basal margins raised and grasping the column. The callus has two raised keels pigmented in dark magenta that basally delimit a narrow canal and further forward diverge to form a tapering fovea with a mucro at its base. Apically, the lip has 3-7 flattened and inconspicuous keels that arise at the terminus of the column. Column is greenish-white, sometimes tinted with sufficient yellow or red to give it a salmon-colored pigmentation with purple spotting over the spine and two or three conspicuous “eyespots” at the apex, wide, strongly appressed to the lip, elliptic-subrhombic, trigonous in cross-section at the base otherwise severely dorsiventrally compressed, succulent and with two wide, extended column wings. The column is dorsally carinate, topped with two lateral but inconspicuous teeth at the apex while ventrally it is deeply sulcate with a longitudinal depression that is delimited by two wide keels covered with transparent conic papillae. Anther cap is pale yellow.

Endemic to Western and Southwestern Mexico in the Rio Balsas Basin and the Pacific Coastal Plain in the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima, Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca and Mexico State. There are unverified reports of the species growing in the states of Puebla and Morelos but no suitable herbarium specimens from these stations can be located; and these reports are probably cases of mistaken determinations or confusion about the collecting locality. This species is extremely infrequent in Jalisco, Colima and Nayarit and perhaps many reports of its presence in Western Mexico can be ascribed to incorrectly identified plants of B. barkeriola instead. The two species are easily confused and determining desiccated herbarium specimens is very difficult, even for specialists. The redoubt of this species is undoubtedly Southwestern Mexico since most specimens are known from inland basins in Michoacán, Guerrero and Mexico State in an area known as the Tierra Caliente. There are some stations known in Oaxaca, too, but the size of the population there falls off dramatically towards the southern part of its range.

This species is widespread throughout Mexico and can have huge populations at its stations, but these are discontiguous and there are large expanses of seemingly suitable habitat with no plants located between them. Barkeria uniflora seems to require a highly-particular ecological niche for its establishment with just the correct balance of humidity, light, ventilation and specific porophyte availability. When these conditions are just right, the species is rampant and plant populations in the thousands per hectare are possible.

This plant grows as a twig-epiphyte in savannas, tropical deciduous forest and warm Pinus–Quercus forest. The species has a high porophyte specificity and often will be seen growing exclusively on certain tree species at its stations. These tree species are often Crescentia alata, Bursera spp., Pithecellobium dulce, Spondias purpurea, Psidium molle, and Randia sp. It is rare to observe this species growing near water sources or in gallery forest. Its preference is to become established in a savanna on a solitary tree isolated from other trees on a well-ventilated branch tip. Occasionally the plants can become established on columnar cacti, as well. The plants prefer brutally hot days but surprisingly cool nights in areas subject to torrential monsoon rains practically every night during their brief growing season. The plants are very difficult to spot since the cane-like pseudobulbs look like tree branches. It is common to first spot the roots snaking down the branches and only afterwards trace their origin back up to the plant. Like many other Barkeria species, this taxon tolerates human disturbance and so it will frequently become an invasive but beautiful “pest” in Citrus sp. or Psidium sp. groves near dwellings.

The altitudinal band between 900-1,100 meters is the preferred elevation for this species. Barkeria uniflora seems to grow best in areas with hot, dry days but cooler nights and so it likes to creep up the slopes of the foothills of the Pacific Coastal Plain. Cool night temperatures enhance both the size of its flowers and the intensity of the pigmentation. It will grow as low as 500 meters, but this is infrequent. Likewise, it will also grow as high as 1,450 meters. This elevation on the Pacific Coast generally marks the ecotone between the tropical deciduous forest and warm oak forest. It will not establish at higher elevations in oak forest.

Owing to its wide distribution, this species is frequently seen with other Barkeria species of the Obovata section in some areas of Guerrero, Michoacán and Oaxaca. Most of the species in the Scandens group, on the other hand, are more temperate in their climatological requirements and tend to grow at higher elevations. Thus, their populations do not intermingle with B. uniflora. The only exception that we are aware of is a small area near Jungapeo, Michoacán where B. scandens was observed growing on rocks directly above a large population of B. uniflora. The species in the Obovata section are easily identified even out of flower on account of their fusiform pseudobulbs and bushy, caespitose habit. In contrast, the pseudobulbs of B. uniflora are cane-like and they are mostly the same diameter throughout their length. Also, the inflorescences of B. uniflora only branch distally and in a manner quite distinct from the species in the Obovata section. In practice, the only other Barkeria species that could be confused with this species are its cousins in the Uniflora section: B. dorotheae, B. shoemakeri and B. barkeriola. Superficially, B. dorotheae looks very similar to B. uniflora but owing to the hyper-restricted distribution of the former, these two plants would never be observed in the same area. Thus, biogeographical data about the collection site would be sufficient to exclude B. dorotheae from consideration as a candidate of an unknown but wild-collected Barkeria plant. Barkeria shoemakeri tends to grow lower and hotter than B. uniflora, and is more commonly seen closer to the Pacific coast than in inland valleys. If in-situ plants are encountered with foliage the leaves in B. shoemakeri are much more succulent and lanceolate than the leaves of B. uniflora. Also, the leaves and stems of B. shoemakeri exhibit stippling with purplish-red pigmentation, a trait that has only rarely been observed in B. uniflora. Overall, the species most likely to be confused with B. uniflora is B. barkeriola. This is surprising since these two species are almost completely allopatric except for small overlapping populations near Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. The species can grow together in that area and apparently do not hybridize or have intermediate forms so the barriers to speciation are well-established. Plants of B. barkeriola grow lower and hotter than B. uniflora and also nearer to the Pacific coast. Vegetatively, plants of B. barkeriola also exhibit the purplish-red stippling along the surface of their stems that can be observed in B. shoemakeri, but that is almost never seen in B. uniflora. In terms of their flowers, B. barkeriola has smaller flowers than B. uniflora, the column is narrower and more heavily marked with dark lines, the blotch is smaller but more intensely colored, the lip is convex so as to form a cushion, and the tepals are arranged in a half-circle such that the lateral sepals do not extend past 180 degrees. These characters are well-documented and quite easily seen when examining the two species next to each other, but for the tyro it can be difficult to tell them apart when examining a photograph or herbarium specimen.

This species produces its first flush of flowers between October and December, but it appears that the first two weeks in November seem to be the absolute peak bloom period with the majority of plants in the field flowering at that time. Barkeria uniflora is a remontant species so after the first flush of blooms fades, plants will develop new side branches from dormant nodes on their inflorescences which, in turn, will produce additional flowers perhaps 6-8 weeks later. This characteristic is seen in both wild and cultivated clones and is a shared trait among species in the Uniflora section.

This species is not at risk according to the Mexican government and does not merit any special protection. As mentioned previously, the species is widespread throughout Southwest Mexico with some localities having thousands of plants. If the species were not so difficult to grow, it would probably be more desired by collectors. But at present, there is limited trade in this species owing to its exacting culture requirements, and the fact that most of its range overlaps with drug cartel territory makes acquiring plants in the field a risky proposition for wildlife traffickers.

Barkeria uniflora is a beautiful species undoubtedly, but it is an extremely finicky plant for collectors to grow. James Bateman, author of The Orchidaceae of Mexico and Guatemala, was keenly aware of its intractable nature and wrote:

Barkeria elegans is among the most refractory of the [genus]. To maintain it alive is all that the utmost skill of the cultivator is able to accomplish.

Fortunately the plant’s obstinate cultural requirements are less taxing when it is hybridized with other Barkeria species. The principal characteristics that growers are seeking by cultivating this species are their dramatic coloration and the size of their flowers. The characteristic blotch on the apex of the lip and the “eye spots” on the column will typically be conserved in F1 hybrids, but size is not a trait that is easily inherited by progeny. Many times we have seen enormous B. uniflora clones that measure 8.0-8.5 cm in diameter fizzle when crossed with other plants. There are also many B. uniflora clones, principally those from Michoacán, that have poor texture in the tepals and whose segments are floppy or droopy. Another negative feature of many clones of this species is the propensity for the lateral margins of their lip to fold in on itself, so instead of having an attractive, flat lip a breeder gets something that looks like a horse saddle. The folding lip trait is strongly dominant and almost impossible to breed out of a line, so breeders must work with selected parents with flat lips. Most frustratingly, many F1 hybrids are pollen sterile and so crafting breeding lines using this species is very difficult because there are a lot of dead ends.